Information about Vaccines

Why Should I Get Vaccinated? I Wear a Mask and Practice Social Distancing.

Masking, frequent hand washing, and social distancing are important tools in the fight against COVID-19. For the first year of the pandemic, they were the only protection we had. They are still the only protection for people who do not have access to the vaccine and continue to be important preventive measures. However, the World Health Organization warns that these precautions do not protect you to the same extent as being full vaccinated—which includes the recommendation to get a booster shot.

What's the Difference Between the Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson Vaccines?

All three vaccines teach your immune system how to recognize the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Your body uses this information to develop an immune response that prepares you to fight off an infection. The key differences between the vaccines are in the exact contents of the vaccine and how much of the vaccine is administered with each dose. It is important to understand that the vaccines are all extremely successful at fighting against the COVID-19 virus.

Are Other Vaccines Coming?

Yes! There are many different vaccines in development. In the United States, Novavax is in the process of applying for emergency authorization of their vaccine.

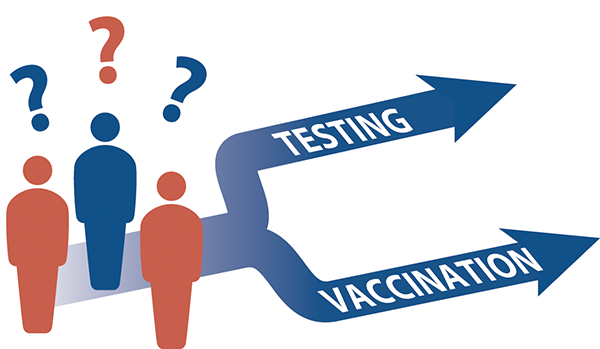

Instead of Getting Vaccinated, Can't I Just Get Frequent COVID-19 Tests?

Testing is an important tool for controlling the spread of COVID-19, but it does not prevent you from infection. Testing will verify that you were negative for the virus at the time you were tested. It’s a snapshot of your health at that exact moment. It does not guarantee that you will not become infected in a crowded elevator or a coffee shop the moment you leave the testing site. And it does not keep you from spreading the virus to other people.

Think of it this way: if you wear sunscreen at the beach, you will likely avoid a serious sunburn. Or, you could check your shoulders every time you come home from the beach to look for signs of a sunburn. The sunscreen, like a vaccine, is designed to prevent harm. Examining your skin, like a COVID-19 test, only tells you after the fact, and once you’ve gotten a sunburn, all you can do is treat the symptoms and wait for it to go away.

Now imagine a sunburn that is contagious: you scorch your skin at the beach, and then you spread that pain and misery to your family, friends, or coworkers. According to this opinion piece in Scientific American, we don’t talk enough about the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing transmission of the virus: “vaccinating a large majority of Americans throughout the country is our surest bet for returning to normal. Entirely eliminating spread of the virus may be an unreachable goal, but mass vaccination—in the U.S. and around the world—will relegate COVID to the background of our lives.”

Have You Been Waiting for the FDA to Approve the Vaccine?

Good news! The Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer vaccine for individuals 12 years of age and up. Emergency use is approved for children 5 and up.

The Pfizer vaccine was the first to receive final FDA approval.

As of January 31, 2022, the FDA also granted full approval for the Moderna vaccine for people 18 and older. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is expected to receive full approval soon. For now, Johnson & Johnson and Moderna for individuals 5 to 17 continue to be available under the Emergency Use Authorization. And on February 2, 2022, Pfizer and BioNTech sought approval under the emergency use authorization for COVID-19 vaccines for children 5 and younger—currently the only age group not eligible for the shots. A decision is expected within weeks.

Are There Medications I Can Take Instead of Getting Vaccinated?

Two antiviral medications, molnupiravir (Merck) and Paxlovid (Pfizer), have been given FDA emergency use authorization for treatment of COVID-19 in some patients.

These medications can be taken by mouth and work to block replication of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Both medications have been shown to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, they are only helpful if taken early during illness, within a few days of symptoms appearing.

Although molnupiravir and Paxolovid, as well as the previously authorized intravenous antiviral remdesivir and monoclonal antibody therapies are useful in treating COVID-19 illness, they cannot be used in place of vaccination. Think about the analogy of COVID-19 illness and sunburns discussed earlier: using sunscreen can prevent sunburn, whereas using aloe vera and pain relievers can treat the sunburn and relieve symptoms. Likewise, vaccination can block infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and so prevent COVID-19 illness, whereas molnupiravir, Paxolovid, remdesivir, and monoclonal antibody therapies can only be used to treat COVID-19.

Your best bet for preventing illness from COVID-19 in yourself and the potential for spreading it to others is still vaccination and boosters.

Why Should My Young Children Be Vaccinated?

Young children seem to be as likely as adolescents and adults to be infected with COVID-19 and to spread the virus, even though they seem to be less likely to become seriously ill.

Reports of COVID-19 cases among children have spiked dramatically across the United States during the recent omicron variant surge. For the week ending January 20th, nearly 1,151,000 child COVID-19 cases were reported. This represents a 17% increase over the 981,000 added cases reported the week ending January 13th and a doubling of case counts from the two weeks before. More than 10.6 million children have tested positive for COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic.

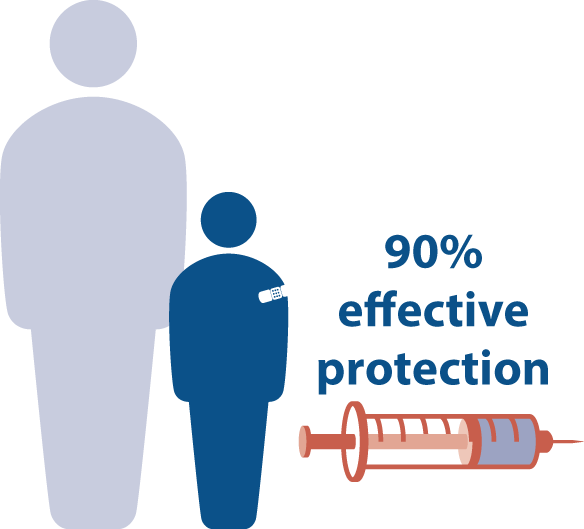

In studies done among thousands of 5- to 11-year-olds, results showed the Pfizer vaccine had no severe vaccine-related side effects or dangerous allergic reactions. The Pfizer vaccine was found to be more than 90% effective at protecting this age group from contracting symptomatic COVID-19.

When and Where Can My Children Get Vaccinated?

The FDA gave the Pfizer vaccine emergency use approval, and the CDC recommended the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine for children 5 through 11 on November 2, 2021.

As of February 2, 2022, Pfizer and BioNTech are seeking approval under the emergency use authorization for COVID-19 vaccines for children 5 and younger—the only age group not currently eligible for the shots. A decision is expected within weeks. Check the CDC website to find COVID-19 vaccines near you.

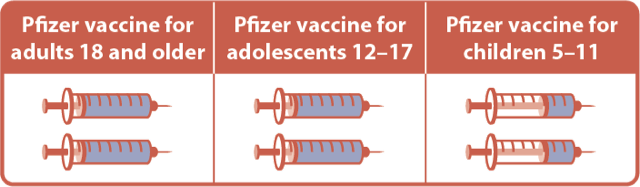

How Many Shots Will My Children Need?

According to the FDA, children will need to receive two shots of the Pfizer vaccine, and these shots should be administered three weeks apart. The dosage for children 5 to 11 is one third the dose given to adolescents and adults.

I'm Pregnant; Will Vaccination Protect Me and My Baby?

Yes! Pregnant people have increased risk of becoming severely ill with COVID-19, and vaccination in this group is both safe and effective. In fact, the CDC and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists both recommend that pregnant people get vaccinated. In addition to protecting you, getting vaccinated while pregnant provides your baby with protection during their first months of life, when they are too young to be vaccinated.

I Hear about Breakthrough Infections: Will I Get Sick Even If I Get Vaccinated?

Breakthrough cases, in which a person who is fully vaccinated becomes infected with COVID-19, do occur. No vaccine is 100% effective. There will always be some people who get sick in spite of getting vaccinated. This happens with the flu shot every year; many people who get a flu shot later come down with the flu, but vaccinated people are typically not as sick as unvaccinated.

According to Macmillan Learning author David Hillis, research shows that vaccinated individuals who get breakthrough infections are less likely to become seriously ill, and in fact may be asymptomatic—they may not actually feel sick. Hillis writes, “the severity of any illness is likely to be worse in unvaccinated individuals. So even though the vaccines are not 100% effective at preventing illness, they greatly reduce your chances of getting sick, as well as reducing your chances of severe illness… Eventually, as more of the human population is vaccinated, the virus epidemic is expected to die out. When few people are susceptible to infection, the virus can no longer find new hosts to infect, and the epidemic will be over” (Hillis, David, “Immunizations and Booster Shots,” Mason County Science Corner, Mason County News, August 25, 2021).

Vaccinated individuals are also much less likely to infect others, including vulnerable people who are unvaccinated.

What Are the Vaccine's Side Effects?

Many people are concerned about the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine. All vaccines, and indeed all medications, carry some risk of side effects. It’s important to be aware of those risks, according to Jennifer Punt, a Macmillan Learning author and University of Pennsylvania immunologist. In this video Dr. Punt speaks plainly about the risk of side effects from the COVID-19 vaccine versus becoming infected with the virus.

Side effects may include pain, redness, and swelling around the area where you received the shot (typically, your arm), and fatigue, headache, muscle pain, fever, chills, and nausea. For most people, side effects only last a day or two. Side effects are typically worse after the second dose. The discomfort is a sign that your body is developing an immune response that will protect you if you are exposed to the virus.

For some people, side effects may be greater. In this video, Macmillan Learning author and Pomona College professor of biology Sharon Stranford describes the typical side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines. If you have concerns about potential side effects from the vaccine, talk to a qualified medical professional before you receive your first jab.

What about the Rumors that the Vaccines Are Dangerous?

There are a lot of rumors about the COVID-19 vaccines. Some of this information is inaccurate and dangerous, but may sound convincing. According to Macmillan Learning author and University of Pennsylvania professor of immunology Jennifer Punt, we are all susceptible to misinformation.

Let’s look at the rumors one at a time.

The vaccine will give me COVID-19. This is a common concern based on the fact that in the past, some vaccines contained live virus particles. None of the COVID-19 vaccines used in the United States contain live COVID virus, and so they cannot give you the disease. Instead, as described in this article from the CDC, vaccines prepare our immune systems to fight off the disease if we are exposed. That is why some people feel ill for a day or two after receiving the vaccine.

The vaccine can affect fertility, pregnancy, or sexual function. According to Scientific American, “studies so far have not linked the vaccines with problems related to pregnancy, menstrual cycles, erectile performance or sperm quality. The evidence does show that COVID-19 can involve problems in all of these areas.” The CDC recommends that pregnant and breastfeeding women be vaccinated against the virus. Because of changes to the immune system during pregnancy, pregnant unvaccinated women are five times more likely to contract the virus than an unvaccinated woman who is not pregnant. What’s more, having the virus during pregnancy is more likely to make you seriously ill.

The vaccine causes dangerous blood clots. There is a very slight risk of developing blood clots after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, studies show. However, this study cited in the British Medical Journal found that the risk of blood clotting events after infection with COVID-19 is much higher than the risk posed by vaccination.

Beware of false or misleading information. This article in the journal Nature lists eight ways to spot misinformation.

The organization #ScienceUpFirst is a Canadian-based group of independent scientists and health care professionals focused on sharing the best available science with the public. You can follow them on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok: @ScienceUpFirst. They also post in French: @LaScienceAbord.

Want to learn more, or have questions about things you’ve heard about or read about? The World Health Organization (WHO) has a comprehensive list of myths about COVID-19 and vaccines.

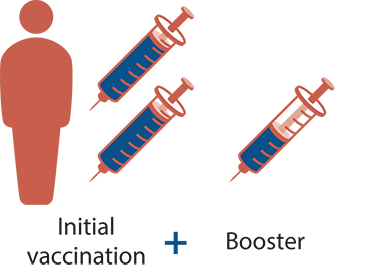

What Is a Booster Shot, and How Does It Differ from the Initial Vaccine?

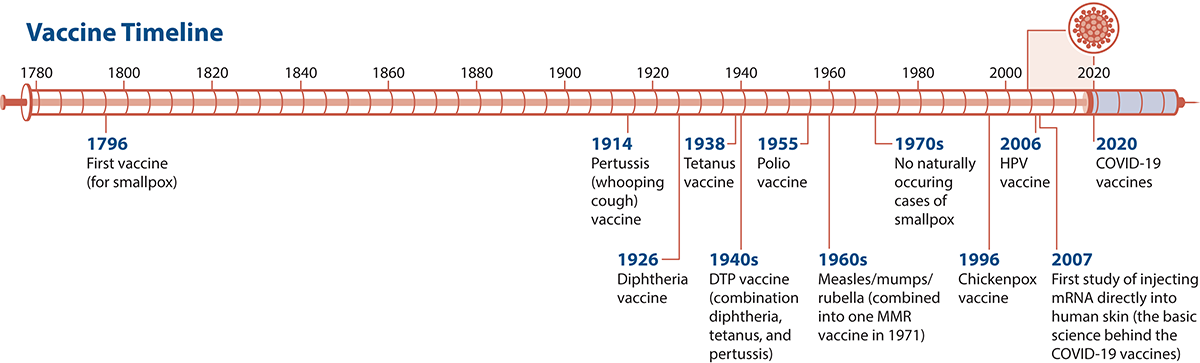

When you get a vaccine, you are teaching your immune system what a particular invading bacteria or virus looks like. If the bacteria or virus appears again in the future, your body can keep you healthy by quickly recognizing and destroying it. Your immune system protects you by developing a defense that includes antibodies (blood proteins produced by your body to counteract germs) and important immune cells. To help your body produce an effective immune response, many vaccines need multiple doses, usually spaced out over a few weeks or months. In some cases this is enough to protect you for a lifetime. More commonly, though, your body needs occasional reminders to keep up its defenses, and these reminders come in the form of booster shots. You’ve probably received a booster shot of a vaccine before–for example, booster shots to protect against tetanus are recommended every 10 years, during pregnancy, and when certain injuries occur.

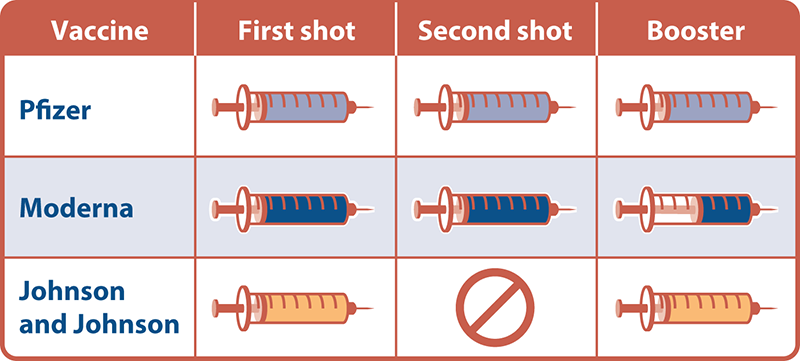

The booster shots of both the Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson vaccines are the same as the shots used for initial vaccination: the same substance and the same dose. For the Moderna vaccine, the substance is the same but a smaller dose is used in the booster shot than in the initial series.

Will I Need a Booster Shot?

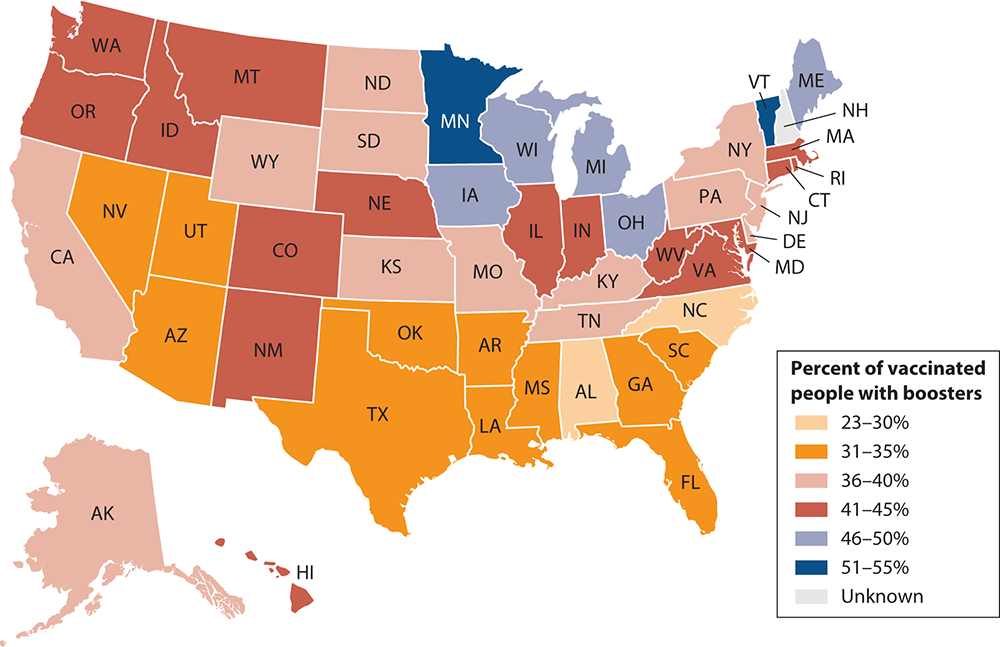

Currently, you do not need to get a booster shot to be considered fully vaccinated. However, the CDC has recommended booster shots for everyone age 12 and up. The timing of when to get a booster shot and which one you can get vary. The most current information can be found on the CDC’s website.

- For people who received two doses of either the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, the CDC recommends a booster shot at least six months after the second shot.

- For people who received one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, anyone over the age of 18 is recommended to get a booster shot at least two months after the initial vaccination.

My Immune System Is Compromised; What’s Recommended for Me?

For some individuals with compromised immune systems, vaccination guidelines may include additional doses. For more information, you can consult the CDC’s website or contact a trusted healthcare provider to discuss what’s best for you.

I'm Eligible for a Booster Shot. Does It Matter Which One I Get?

What Are the New Guidelines for Isolating If Infected with COVID?

Previous CDC guidelines called for a full 10 days of isolation after a positive diagnosis of COVID-19. The CDC now says that infected people can end isolation after 5 days if: (1) they are asymptomatic or (2) their symptoms are going away and they have no fever. After the 5-day isolation, individuals are advised to wear a mask around people at all times and to avoid traveling for another 5 days.

What Should I Expect When I Return to Work Onsite?

Many people are anxious about returning to a worksite where they will be in close quarters with their colleagues. After almost 2 years of isolation, returning to work will require a psychological and physical adjustment, as noted in this Scientific American article. The safest way to return to a shared work space is to:

- Get vaccinated. Doing so protects you and the people around you, some of whom may not be able to receive the vaccine for medical reasons.

- Get your booster shot.

- Wear a mask when you’re indoors.

- Practice social distancing when possible. Spread out in meetings, and don’t crowd the elevators. Give everyone some space.

- Wash your hands frequently.

- Observe testing requirements.

- If you’re not feeling well or you or a family member is exposed to the virus, stay home and arrange for a COVID-19 test. Don’t come back to work until you are cleared to do so by a medical professional and by your employer.

For more information about how your employer or campus is addressing a return, please contact your Human Resources or Campus Safety and Administration departments.